|

CURTAIN UP, LIGHT THE LIGHTS: 1874-1900 by Scott Miller Note: This is a chapter written for the book Strike Up the Band: A New History of Musical Theatre, but cut prior to publication.

Many musical theatre books, many teachers, many cognoscenti will tell you the American musical theatre began with The Black Crook in 1866. Don’t believe a word they say. The Black Crook was an overblown dramatic spectacle more about sets and special effects than anything else, haphazardly using popular songs, into which the producer inserted a French ballet company that had been booked into another theatre that had burned down. The result was an endless mess of an evening that had nothing whatsoever to do with musical theatre as we know it today. Nothing. It was not a musical. It was not a precursor to musical theatre in any legitimate sense. It was just an accident and a mess. Forget about it. Of course, the precise beginnings of musical theatre are hard to trace, mostly because musical theatre had no precise beginnings. After all, we know that music was used in theatre by the classical Greeks and Romans, by Shakespeare, and by most other dramatists. Theatre used music; that’s all there was to it. It was only toward the end of the 1800s that the distinction emerged (which still survives today) between "legitimate" theatre and musical theatre. The idea of theatre without music was unheard of until the late 1800s, and up to that point, audiences did not believe, as many do today, that theatre using music was less "legitimate." Even in America, the roots go back a long way. Scholar O.G. Sonneck is pretty sure the first theatre piece with music in America was a British ballad opera in 1703 (the records are sparse). We know for sure a ballad opera was performed in Charleston in 1735. Historians are relatively sure that the first American-written theatre piece with music was a comic opera called The Disappointment, which almost opened in Philadelphia in 1767. For some reason still unknown, it was canceled. And so the strange history of American theatre with music began. But Strike Up the Band isn’t about theatre with music. It’s about what we know today as "musicals" or "musical theatre," a category that does not include opera, ballad opera, operetta, revues, or plays with music stuck in. Today, musical theatre is an art form separate from theatre that lacks music, distinct in its history, evolution, performance style, and its practice. And with today’s definitions in mind, we can now look backward and see the roots of this art form which we love and enjoy today. To get where we are now from where we were then, lots of things had to happen. Audiences had to demand characters and plots that reflected their real lives and issues, lyricists and bookwriters had to learn to write in the language of everyday people; composers had to learn to write in a style accessible to its audience and to create original scores that didn’t scavenge existing pop music or old, worn out European traditions; and directors and actors had to discover the style of acting and staging we now recognize (even if unconsciously) as musical theatre – fast, brash, energetic, intense, emotional, and presentational. The truth is that there weren’t any shows that were actually what we know as musicals until the very end of the 1800s, but there were some shows that were awfully close a little earlier than that. In the Beginning

It was the first time anyone has used the term "musical comedy" to refer to an American stage show. Evangeline was no great work of art by any measure, but it remained popular, in various revivals and tours, for thirty years. In 1880, an unnamed critic in the Dramatic Mirror wrote, "The vitality of the extravaganza is something wonderful, considering the length of time it has been before the public. Some of the old, pointless puns and gags have been eradicated, only to be replaced by new puns and gags just as witless and just as inane as their predecessors. When it is all over, the question arises, What is there in Evangeline that should ever have gained for it the amount of public favor it has enjoyed?" Still, in 1885, it returned to the New York stage again and ran for what was then an incredible 251 performances, followed by another successful tour In 1879, perhaps the most direct ancestor of American musicals opened, a new piece called The Brook by Nate Salsbury, the first full-length musical with a fully American story, topical humor, a relatively coherent plot, and contemporary American styles of music, dance, and dialogue (although its score was not original). Evangeline was written by Americans, but the music still sounded like operetta. The Brook sounded American. It rejected all the conventions of European operettas. Interestingly, it appeared in New York only after a long national tour, making notable stops in St. Louis (where it premiered in 1877), Chicago, and San Francisco. It was labeled a "laughable and musical extravaganza," but it was something close to what we now call musical comedy. Its slight plot told of five members of an acting company, taking a trip down a river for a picnic, with lots of obstacles and mishaps along the way. What’s important about this show is that it was about ordinary American people – no Europeans, no royalty, no rich people. It was the closest we had yet come to real musical comedy. After a successful New York run an another national tour, the producers took the show to England, the first time an American musical comedy has played Europe. But more important than The Brook’s innovations is the fact that it was a big hit and everybody started imitating it. It started a new fashion in New York theatre, and musical comedy was born. Its appeal to producers was in the low cost of sets and costumes and the ease in casting – there were no special talents needed for this new form, no operatic singing, no jugglers, no trained dancers, no spectacle to create. It was about ordinary people in an ordinary world. What could be easier to put on a stage? Throughout the history of musical theatre, innovation pops up everywhere, but it only counts when the show doing the innovating is a hit. No one copies a flop. No one rushes to imitate a show that loses money. For things to change, an innovative show has to be a financially successful one as well, so that others will follow down the new path. The truth is that producers don’t care about advancing the art form. They never have and they never will. They care about selling tickets. So if an innovative new show sells tickets, every producer in town will want something just like it. Up until this point, strangely enough, the top producers and the top composers didn’t think America was a very interesting topic for their work. Even American writers would write about exotic locales and royalty. But the successes of shows like Evangeline, The Brook, The Tourists in the Pullman Palace Car, and others, convinced producers and composers that Americans in American settings could indeed be interesting subject matter for their work. The purveyors of the lower forms of entertainment learned this lesson long before this time, but the people writing the most intelligent, most artistic shows were just finding this out. Indeed, the dawn of the American musical was upon us. Of course, by the 1890s, writers and producers were starting to call their shows whatever they wanted – the terms burlesque, farce-comedy, musical comedy, and extravaganza were being used almost interchangeably. So the term musical comedy started appearing everywhere, even though the shows it described weren’t usually musical comedies. Black and White

The Gaiety Theatre in London, under the guidance of George Edwardes had been home to burlesque, operettas, comic operas, dramas, comedies, pretty much everything. In 1892 Edwardes opened a proto-musical called In Town, which the Sunday Times called "a curious medley of song, dance, and nonsense, with occasional didactic glimmers, sentimental intrusions, and the very vaguest attempts at satirizing the modern masher about town." It wasn't exactly a musical like we think of musicals, but it was close. Then in 1893, the theatre presented another proto-musical comedy, A Gaiety Girl, by James Davis (writing under the name Owen Hall) and Sidney Jones. Its plot was a crazy quilt of mistaken identity, imposters, villains, class barriers, and a day at the beach, elements that showed up in dozens of musicals in London and New York in subsequent seasons. Of course, London wasn’t quite sure what to make of this new form. The Era called A Gaiety Girl "one of the most curious examples of composite dramatic architecture that we have seen for some time . . . but it is always light bright and enjoyable." When it came to America, the Dramatic Mirror called it "really an indefinable musical and dramatic mélange," and it consisted of, he said, "sentimental ballads, comic songs, skirt-dancing, Gaiety Girls, society girls, life guards, burlesque, and a quota of melodrama." So it was a bit of a mess. But it was such a big hit, fourteen more shows were written, all with Girl somewhere in the title. One of those follow-ups, The Shop Girl, was written by American journalist Henry Dam and Belgian composer Ivan Caryll. The Shop Girl went on to run 546 performances in London, but barely more than 60 performances on Broadway. Still, it played Australia, Paris, Vienna, and elsewhere around the world. Some English scholars call The Shop Girl the first real musical comedy because of the integration of its script and score. Edward Rice and his new partner Augustin Daly opened their imitation of The Gaiety Girl in 1896, a new musical comedy called The Geisha, a show full of the same light-hearted, sophisticated, urban brand of humor. Daly truly understood the lightness of touch and speed of pace that would soon come to define American musical comedy, and he proved it again in 1898 with A Runaway Girl.

Black performers finally joined the fun with two all-Black musical comedies in 1898, A Trip to Coontown and Clorindy, The Origin of the Cakewalk. The big break for Will Marion Cook and Laurence Dunbar’s Clorindy is described by composer Will Marion Cook in his autobiography. "I went to see [producer] Ed Rice," he wrote, "and I saw him every day for a month. Regularly, after interviewing a room full of people he would say to me (I was always the last): ‘Who are you and what do you want?’ On the thirty-first day – and by now I am so discouraged this is my last trip – I heard him tell a knockabout act: "Come up next Monday to rehearsal, do a show, and if you make good, I’ll you on all week. "I was desperate. On leaving Rice’s office, I went at once to the Greasy Front, a Negro club run by Charlie Moore, with a restaurant in the basement managed by Mrs. Moore. There I was sure to find a few members of my ensemble. I told them a most wonderful and welcome story: we were booked at the Casino Roof! That was probably the most beautiful lie I ever told. "On Monday morning, every man and woman, boy and girl that I had taught to sing my music was at the Casino Roof. Luckily for us, Ed Rice did not appear at rehearsal until very late. that morning. By this time, my singers were grouped on the stage and I started the opening chorus. When I entered the orchestra pit, there only about fifty people on the Roof. When we finished the opening chorus, the house was packed to suffocation." Blacks were finally on Broadway and, most important, not as minstrels and not in black face. Clorindy was the first show created and performed entirely by blacks in a "mainstream" theatre for an exclusively white audience. After Clorindy’s opening, Will Marion Cook exclaimed, "Negroes are at last on Broadway, and here to stay!" Cook had not just put blacks on Broadway, he had also put syncopation into Broadway’s musical vocabulary for the first time, something that would distinguish musical comedy music from opera or operetta, forever separating the two, marking perhaps the most important musical moment in the history of Broadway. Cook would go on to write scores for many more musicals, including In Dahomey (1903), Abyssinia (1906), and Bandanna Land (1908), which the Dramatic Mirror called "one of the rare plays that one feels like witnessing a second time." A Trip to Coontown not only boasted an all-black cast, but also Broadway’s first black producer, Bob Cole. The show's title a conscious reference to the very popular A Trip to Chinatown, it told the story of a black con man who tries to con an older black man out of his $5,000 pension. The story was only barely important, and the show only marginally figures in the development of the American musical, except for the fact that it was the first musical produced, directed, written, and performed by blacks. And producer Cole, after only modest success with Coontown, was determined to push black musical entertainment into new, unusual, and exciting places.

Also in 1899 in London the very successful A Chinese Honeymoon opened, written by George Dance and composer Howard Talbot, becoming the first English musical show to run over a thousand performances. Its very silly story involved an English couple in China, a impetuous kiss, wacky foreign rules about public kissing, and a rescue by the British Navy. Of course, as usual, when the show came to Broadway its American producer interpolated new songs by William Jerome and Jean Schwartz. It was the first show produced on Broadway by one of the future giants of Broadway producers, Sam S. Shubert, one of the soon-to-be-legendary Shubert Brothers. Still, we had not yet seen full-blooded, modern, American musical comedy as we know it. That would be coming soon from George M. Cohan. The critic for the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News wrote in 1899, "It seems difficult in any one musical comedy to get away from the musicals which have preceded it. The personages always seem to be doing much the same sort of thing in much the same sort of way. I am not sure whether the special class of playgoer for whom musicals are written would appreciate a genuine new departure. I should not like to say even that they would understand one." Whether or not that was true, a departure was coming, whether or not anyone could see it coming. In 1902, The New York Times would run the headline, "Musical Comedies’ Vogue Said to Be on the Wane." They were wrong. Cohan was changing everything. ______________________________________ Copyright 2008. Cut from Scott Miller's book, Strike Up the Band: A New History of Musical Theatre. All rights reserved. Miller is also the author of Deconstructing Harold Hill, Rebels with Applause, Let the Sun Shine In: The Genius of HAIR, From Assassins to West Side Story., and Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and Musicals. |

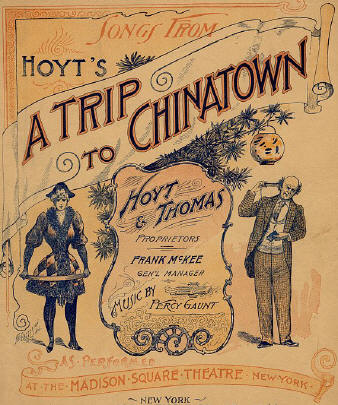

In 1890, Charles H. Hoyt and composer Percy Gaunt’s

musical A Trip to Chinatown debuted at the Madison Square Theatre and

racked up a long-run record for continuous performances that stood for

twenty-eight years – 657 performances, an unheard of run at that time. The plot

(in which no one ever goes to Chinatown by the way) involved two men in San

Francisco planning a double date of dinner and dancing with their lady friends

and (of course) a chaperone. But they don’t want their strict merchant father

along to ruin everything, so they tell him they’re going on an educational trip

to the city’s Chinatown (thus working America’s current preoccupation with all

things Oriental into the title of a show that had nothing at all Oriental in

it). Unfortunately, the young widow who is to be coupled with one of the young

men sends a note of confirmation and it gets accidentally delivered to the

father, who thinks he’s got a date with the girl. Comedy ensues, of

course, and just as predictably, the irascible old man somehow winds up with the

bill but can’t pay it because he’s lost wallet. Wait a minute, you cry, that

sounds an awful lot like Hello, Dolly! (1964). Why yes it does. A Trip

to Chinatown is based on the 1835 British farce A Day Well Spent, the

same source for Thornton Wilder’s 1938 comedy The Merchant of Yonkers,

which was expanded in 1955 into the full-length The Matchmaker, which was

then adapted in 1964 into the musical Hello, Dolly! A Trip to Chinatown

was also the first American musical show to have three breakout hit songs, "Reuben and

Cynthia," "The Bowery," and "After the Ball" (which wasn’t actually written for

this show). The show toured the country first, then ran on Broadway for 657

performances, becoming the longest running American made show up to that

time. It then ran in London for 125 performances.

In 1890, Charles H. Hoyt and composer Percy Gaunt’s

musical A Trip to Chinatown debuted at the Madison Square Theatre and

racked up a long-run record for continuous performances that stood for

twenty-eight years – 657 performances, an unheard of run at that time. The plot

(in which no one ever goes to Chinatown by the way) involved two men in San

Francisco planning a double date of dinner and dancing with their lady friends

and (of course) a chaperone. But they don’t want their strict merchant father

along to ruin everything, so they tell him they’re going on an educational trip

to the city’s Chinatown (thus working America’s current preoccupation with all

things Oriental into the title of a show that had nothing at all Oriental in

it). Unfortunately, the young widow who is to be coupled with one of the young

men sends a note of confirmation and it gets accidentally delivered to the

father, who thinks he’s got a date with the girl. Comedy ensues, of

course, and just as predictably, the irascible old man somehow winds up with the

bill but can’t pay it because he’s lost wallet. Wait a minute, you cry, that

sounds an awful lot like Hello, Dolly! (1964). Why yes it does. A Trip

to Chinatown is based on the 1835 British farce A Day Well Spent, the

same source for Thornton Wilder’s 1938 comedy The Merchant of Yonkers,

which was expanded in 1955 into the full-length The Matchmaker, which was

then adapted in 1964 into the musical Hello, Dolly! A Trip to Chinatown

was also the first American musical show to have three breakout hit songs, "Reuben and

Cynthia," "The Bowery," and "After the Ball" (which wasn’t actually written for

this show). The show toured the country first, then ran on Broadway for 657

performances, becoming the longest running American made show up to that

time. It then ran in London for 125 performances. In 1897, The Belle of New York, by Charles

Morton Stewart McLellan (writing as Hugh Morton), opened on Broadway and ran a

disappointing fifty-six performances. It went on a mildly successful American

tour and then headed for Europe. In London the show ran for an astonishing 697

performances, the longest running American show ever in London up to that point,

and Londoners fell in love with it, never having seen anything quite like it

before. It was, as much as anything that gone before, profoundly and uniquely

American in its language, pace, and attitude. It went on to successfully tour

Germany, Austria, France, and Australia, for the first time allowing Broadway to

conquer the world’s capitals. The show’s story told of a salvation army girl (a

precursor to Guys and Dolls) who teaches a spendthrift rich boy how to

save his money, much to the delight of his father. The Sunday Times

wrote, "The Belle of New York certainly meets the ever-present want for

novelty but is best described as bizarre. It is like nothing we have ever seen

here, and it is composed of the oddest incongruities of plot. Characters include

sailors and professional pugilists, not to mention twin Portuguese brothers, the

lunatic Karl von Pumpernick and Mr. Frank Lawton whose talent as a whistler

sends the audience into raptures by his clear, sweet, long sustained trillings.

Doubtless the actors here represent types of theatrical people who exist in the

United States, though we have nothing like them on this side of the Atlantic."

It went on to say "it is the brightest, smartest and cleverest entertainment of

its kind that has been seen in London for a long time."

In 1897, The Belle of New York, by Charles

Morton Stewart McLellan (writing as Hugh Morton), opened on Broadway and ran a

disappointing fifty-six performances. It went on a mildly successful American

tour and then headed for Europe. In London the show ran for an astonishing 697

performances, the longest running American show ever in London up to that point,

and Londoners fell in love with it, never having seen anything quite like it

before. It was, as much as anything that gone before, profoundly and uniquely

American in its language, pace, and attitude. It went on to successfully tour

Germany, Austria, France, and Australia, for the first time allowing Broadway to

conquer the world’s capitals. The show’s story told of a salvation army girl (a

precursor to Guys and Dolls) who teaches a spendthrift rich boy how to

save his money, much to the delight of his father. The Sunday Times

wrote, "The Belle of New York certainly meets the ever-present want for

novelty but is best described as bizarre. It is like nothing we have ever seen

here, and it is composed of the oddest incongruities of plot. Characters include

sailors and professional pugilists, not to mention twin Portuguese brothers, the

lunatic Karl von Pumpernick and Mr. Frank Lawton whose talent as a whistler

sends the audience into raptures by his clear, sweet, long sustained trillings.

Doubtless the actors here represent types of theatrical people who exist in the

United States, though we have nothing like them on this side of the Atlantic."

It went on to say "it is the brightest, smartest and cleverest entertainment of

its kind that has been seen in London for a long time." As the nineteenth century came to a close, one of the

most successful of the early proto-musical comedies opened in 1899 in London—Florodora,

with a book by "Owen Hall" (i.e., James Davis) and Frank Pixley, and music by Leslie Stuart. A

year later it opened on Broadway and took New York by storm, running an

impressive 549 performances. Chief among its pleasures was the heart-shattering

"Sextette" – six girls, all exactly 130 pounds, five-foot-four, and either

brunette or red-headed. These six girls, Marie Wilson, Agnes Wayburn, Marjorie

Relyea, Vaughn Texsmith (actually Vaughn Smith from Texas), Daisy Green, and

Margaret Walker, became the most famous girls in America for a short time. Three

of them married rich men who had seen and admired them on stage, and that somehow

made such marriages acceptable for the first time. The action of the show took

place on Florodora, an island in the Philippines where a wealthy American

perfume manufacturer has created a perfume named after the island. Of course he

has stolen the island from a sweet young girl who should have inherited it from

her father. The process of getting it back into her hands occupied the evening.

It was never profound or terribly clever, but there were those six girls… It

toured the nation for years afterward and was revived in 1902, 1905, and 1920.

(In Sunday in the Park with George, George's grandmother Marie claims to

have been a Florodora girl...)

As the nineteenth century came to a close, one of the

most successful of the early proto-musical comedies opened in 1899 in London—Florodora,

with a book by "Owen Hall" (i.e., James Davis) and Frank Pixley, and music by Leslie Stuart. A

year later it opened on Broadway and took New York by storm, running an

impressive 549 performances. Chief among its pleasures was the heart-shattering

"Sextette" – six girls, all exactly 130 pounds, five-foot-four, and either

brunette or red-headed. These six girls, Marie Wilson, Agnes Wayburn, Marjorie

Relyea, Vaughn Texsmith (actually Vaughn Smith from Texas), Daisy Green, and

Margaret Walker, became the most famous girls in America for a short time. Three

of them married rich men who had seen and admired them on stage, and that somehow

made such marriages acceptable for the first time. The action of the show took

place on Florodora, an island in the Philippines where a wealthy American

perfume manufacturer has created a perfume named after the island. Of course he

has stolen the island from a sweet young girl who should have inherited it from

her father. The process of getting it back into her hands occupied the evening.

It was never profound or terribly clever, but there were those six girls… It

toured the nation for years afterward and was revived in 1902, 1905, and 1920.

(In Sunday in the Park with George, George's grandmother Marie claims to

have been a Florodora girl...)